by Mel Wells

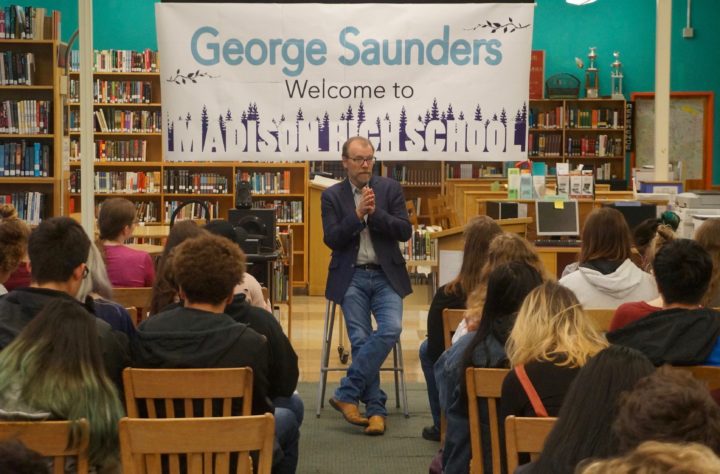

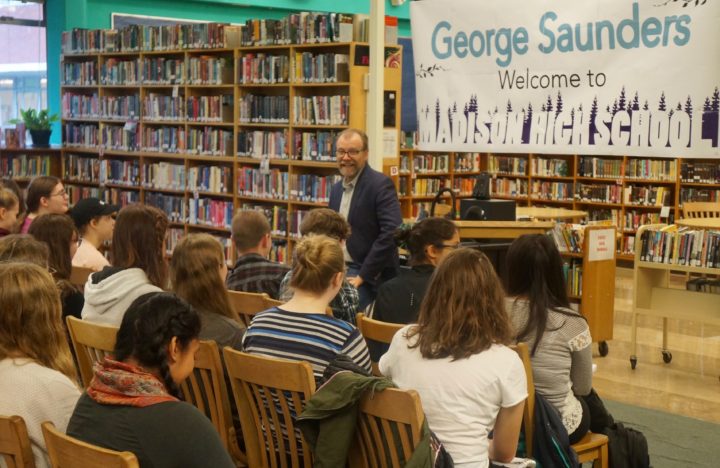

Award-winning author George Saunders had an immediate rapport with students at Madison High School when he visited their library on a rainy Thursday morning. About 95 students came prepared with questions and listened intently to Saunders’ entertaining stories and advice.

After a great introduction by Madison student Carson Flores, Saunders began by relating his journey to becoming a writer, which began in high school. “I was a crap student,” he said, from a working class background in the midwest. He admitted to being “turned on to reading novels” during his junior year by a copy of Atlas Shrugged. “It’s embarrassing,” he said with a laugh, “and I was on a ski trip in Wisconsin and had this sudden idea in my mind of being at college. I was even wearing one of those cheesy university sweaters from fifties.” He paused while students laughed. “But I thought, hey, maybe I could be in that world.”

No one in Saunders’ neighborhood was a writer or artist, he explained, so he had no models for how to make that type of life a reality. Instead of literature, he got a degree in exploration geophysics, which took him to Singapore. He related a story of his girlfriend breaking up with him by mail: “We got these huge stacks of mail once every two weeks, and the first letter was, ‘I love you, etc. etc.,’ and the second was ‘I’m bored.'” Students began to giggle as Saunders related the third letter–the girlfriend had met someone–and the fourth letter, that said she was moving in with this other guy. “In my sadness, I decided to swimming in this river nearby. So I’m in this river, swimming away my sadness or whatever, and I look up at this big oil pipe and see about 300 monkeys on it, and they’re all pooping in the river. And I think, I am swimming in poop.” He ended up coming down with a strange virus that left him sick for two years, “feeling like an 80-year-old man, which meant I began reading a lot more.”

It was during this time that he learned “an essential step in becoming an artist, which is to say, even very quietly to yourself, ‘I’m going to do this.'”

Students bent their heads over their notebooks as they wrote.

“I realized people had done this before,” Saunders continued. “So why not me?”

When a student asked what gave him the idea for Lincoln in the Bardo, Saunders replied that it was an idea he’d had twenty years earlier, back when he was writing “fast, funny sci-fi” and wasn’t sure how to write this other story. But for years, the idea kept coming back to him, often in periods of joy. “The main energizer of art is a feeling of joy,” he said. “A happy, confident feeling of ‘I can do this.'” For Saunders, this feeling and the idea for Lincoln in the Bardo were inseparable, and eventually he felt ready to write it.

Saunders compared the act of writing to that of going on a date with someone. “You’re watching the other person to see how they’re doing,” he said. “If they’re confused, you try to explain better. If you’re losing their attention, then you throw in a fart joke.” The students laughed. “See? It works! Art is simply the process of trying not to suck.”

He paused, and more hands shot into the air. “Why did you use the word ‘bardo’?” asked one student.

“Great question,” he replied. “Bardo is a Buddhist term for a transitional zone, and not just between life and death. We’re in a transitional zone right now, between birth and whatever comes next.” Saunders then told a story about being on an airplane and hearing a huge bang, “like a van plowed into the side of us” and seeing black smoke come pouring out of the left engine. The plane began to drop. “I was totally a good Buddhist at the time,” he said, “and I thought my reaction would be, ‘Well, folks,'” he made his voice steady and calm, “I’ve had a great life…” he began to laugh, “but it wasn’t! Instead I was bargaining, trying to rewind time, to not get on the airplane,” he folded his hands as if in prayer, “I’ll give to charities, whatever. And the only thing that brought me out of it was there was this fourteen-year-old boy sitting next to me and I hear his little voice asking, ‘Is this normal?’ and I said, ‘Yes!'”

The students erupted in laughter.

“A goose had flown into the engine, which apparently they do all the time,” he continued, “but this was a big, buff goose because it took out the left engine, and we continued dropping.” Student leaned in. “And the captain came on and told everyone to stay seated and in buckled up, and I looked at the seat in front of me and thought, I’m going to leave this body.” The room was silent. “And now I’m a ghost,” he said, grinning. When the laughter died down, he assured the students that the plane landed safely, but said that the experience left him ruminating on his relationship with death, “but not in a morbid way. And Lincoln in the Bardo was a way of contemplating death.”

“The next day was the best day of my life,” he noted, “because I saw everything as it is–a temporary miracle. Death didn’t happen that day, but it will happen, for all of us, at some point. Does that make your life terrifying? Sorta. But it’s also an amazing experience.”

“What is your process for coming up with characters?” asked another student.

“The great secret is that you’re riffing,” he replied. “You have to access that part of you that is making up things all the time.” Saunders spoke of his belief that we’re all connected, not necessarily by something outside of us, but because “we all have the same machinery,” he said, gesturing toward his brain.

“How do you write about different socioeconomic classes when you teach at an elite, private university?” asked one student.

“Another great question,” he said. His answer was two-fold: first, that he came from a working-class background “and you never forget what it feels like to not have.” Second, he noted that empathy and curiosity are ways to bridge the gaps between ourselves and other people.

Other questions included how he researched his book, which he said was by casually reading everything that interested him about Lincoln for twenty years and filing away the interesting bits. When asked how he came up with characters for a specific short story, he replied that he’d had a dream about it. “But there are lots of dreams you don’t write about, like a rock band made of skunks,” he added. Saunders also told stories about working on the audiobook, which was challenging with 166 different voices. He read parts himself, and then got everyone from Nick Offerman to people who worked at the publishing house to his own mom to read parts.

“How do you deal with writers’ block?” asked another student.

“You must learn to revise your own work,” he advised, encouraging students to cut it up, move it around, “and you can be happy typing a page of crap because you know you will revise it. In order to become a better writer, you must learn to radically revise your work. Nobody’s first draft is any good.”

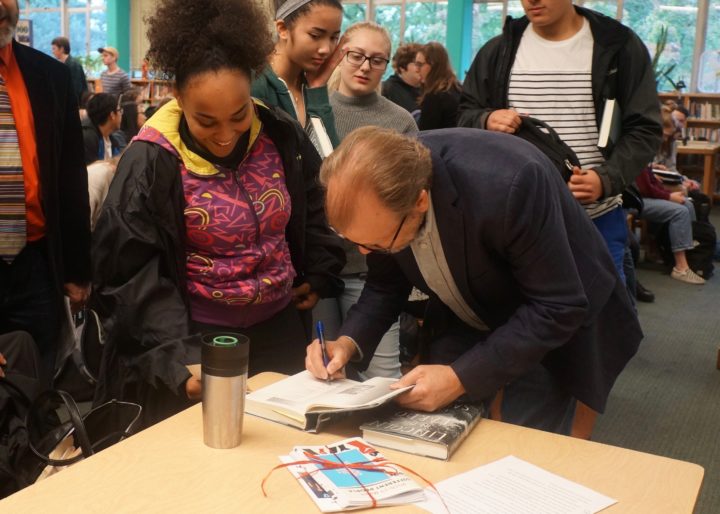

When told that his time with students was ending, Saunders paused the applause for one last bit. “Your questions today were top level,” he said, telling students that they were on par with classes he’d taught at Syracuse. He encouraged them to go to college, even if they didn’t want to be writers, because “the way to get power is to learn to express yourself articulately.” He also stayed afterward, signing books with personalized notes and doodles and acquiescing to selfies.

We’d like to thank Mr. Saunders for being so generous with his time and energy, to librarian Nancy Sullivan for hosting, to teachers Gene Brunak and Erin Tillery for helping their students be so well prepared. Also, huge thanks to the students for their engagement and great questions!