Last week, we shared how Writers in the Schools (WITS) has pivoted to the Distance Learning Model from a programmatic perspective, with a glimpse into a few writers’ video lessons. This week, we wanted to hear directly from a seasoned writer on our roster and learn what the experience has been like for him as a stellar teaching artist who cares deeply about his students and who, like most other cherished writers on our roster, had not previously taught via video lesson.

Monty Mickelson was raised on a steady diet of the fishing, hunting, and hockey in a sleepy southern Minnesota town with a population of 15,000. Although he loved movies and the craft behind them, it wasn’t until high school, after joining the school newspaper, that literature and academics began to pique his interest.

“That staff was comprised of all of the top students in the school, and the editors actually discussed things like homework, tests, books and—Yikes!—college,” says Monty. “I followed some of them to the University of Minnesota. I met my lovely Hellenic wife, Anastasia, in the Journalism program there.”

In college, Monty continued to dive into the craft of writing, ultimately earning a fellowship in fiction writing. From this fellowship was born the foundation and subsequent sale of his first novel, Purgatory (St. Martin’s Press).

Soon after, Monty, Anastasia, and their eldest son headed West and settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico where they lived for several years and saw many milestones including the birth of their second son and Monty’s first teaching experience at a high school summer program. A job offer and the lure of the film industry called, leading the family to begin a new, similarly fruitful chapter in Los Angeles, California in 1999. Just over a decade later, Monty graduated with his MFA from UC-Riverside while his boys headed to college themselves. Many teaching gigs, screenplays, and literary-focused jobs later, Anastasia and Monty, new empty nesters, decided it was time to downsize.

“Our son Anders was already living in Seattle, so the Pacific Northwest seemed enticing,” he recalls. “We knew that we would be politically simpatico with Oregon, so we took the leap of faith in 2014, and have never regretted it.”

Monty has happily taught with WITS since 2016 and completed his first residency, which culminated in a short film script and accompanying short film, at Benson High School. His residency curricula has since typically focused on personal essay writing, short fiction or flash fiction, and an intro to film & television writing. He was in the midst of a spring residency placement at Gresham High School when school closures due to COVID-19 occurred.

Here’s a bit more about Monty and what he has to share about the subsequent transition to distance learning.

Emilly Prado: What has your writing journey been like?

Monty Mickleson: I had several years during which I freelanced for magazines, writing features on travel, pop culture, and (strangely) personal investing. My first staff writer job, just out of J-school, was for a banking trade magazine. The subject matter was deadly boring. One story I researched for that publication involved money laundering in south Florida; that material was the germ of my plot for Purgatory. So that’s a good example of how “everything is fodder”, and even a dreary financial writing job can yield fictional gold!

While I was living in L.A., I wrote or collaborated on more than 20 feature-length movie scripts. Four of those were optioned, and two were filmed. I later came to appreciate that my 20-to-4 ratio was pretty typical for screenwriters.

In addition to Purgatory, I have two other unpublished drafts of novels “in a drawer”. One, titled The Zen Kennel, is a Santa Fe-centric story that was also my graduate thesis. I am presently working on a novel (working title: Virtual Boyfriend) derived from one of my spec scripts.

What initially drew you to the WITS program?

My wife and I attended Portland Arts & Lectures events before I applied for WITS, so I was well aware of Literary Arts’ programming and stature in the community. Also, I never missed Portland Book Festival (FKA Wordstock.) I did not personally know anyone associated with WITS, but the youth programming on the website seemed very familiar to me, having done something so similar with PEN America. I was delighted to get my initial interview and subsequent hire offer.

The WITS: Distance Learning Model was a first for Literary Arts and for you as an instructor. What was the transition like?

I was certainly anxious, primarily owing to my learning curve for self-recording vide lessons and posting worksheets. WITS staff have been most accommodating and patient with me.

The uploading of finished work was not as simple as I had hoped. For instance, after I completed some lessons and went in the shared Google Drive to review them, I found that I had mistakenly selected and uploaded outtakes! So, I had to seek out the intended “print” takes and rectify that.

I have a friend who is a film editor working in Hollywood, and I have a renewed respect for what he does! But seriously, I felt I gained confidence with each successive lesson. Of course, we all feel that deficit of audience, the inability to see how a presentation is “playing.” The only real remedy for that is to try to keep it brief, maintain authority, and try not to stumble over your phrasing.

What has been the most difficult aspect of this transition?

I’d say cutting material, compressing the lesson. Everything I write is golden, all of my anecdotes are fascinating—but only a fraction of it fits!

What has been the best?

The transition is a fresh challenge, and I think all teachers and artists need a few of those. Also, if you feel that COVID is going to rebound in the fall, then distance learning is going to be an essential skill for anyone who desires to teach anything.

What should other teaching artists or organizations consider before making the transition?

It’s a good mental and academic exercise to refine and shorten your lesson to its essence. Some questions for reflection: What skill are you teaching? How long of a definition do you need? Do you need to present more than one example? If you reinforce the point with a video clip, how long does that run, and will you be able to retain student’s attention?

Why did you ultimately choose to adapt with the WITS: Distance Learning Model?

I would refer you back to my line about seeking a fresh challenge and my point about living a good long while with distance learning and social distancing. I also wanted to keep teaching for WITS!

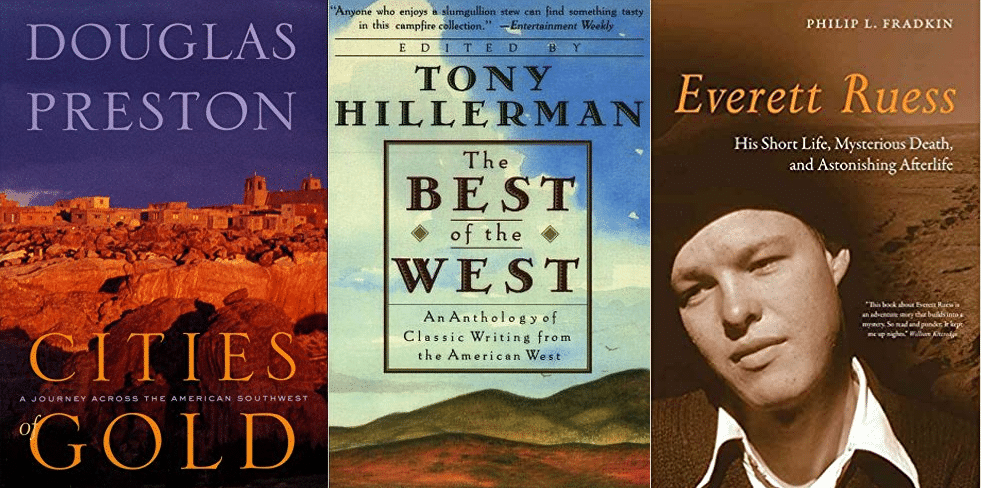

Last, but not least, Monty wanted to share a few of his favorite books to get lost in, in his own words:

I have a great affinity for the American West, its topography, its folklore, its many discreet cultures. I was never a cowboy, but I was related to a lot of them. I have nearly 40 first cousins on my mother’s side of the family, and nearly all of them lived on ranches or farms, competed in amateur rodeos, and generally had a lifestyle that I envied. My affinity was solidified when we moved to Santa Fe in the 1990s. That was my first immersion in an historic, multicultural community. So my three suggested books all arise from those Santa Fe years and my greatly expanded perspective on indigenous cultures.

Cities of Gold by Douglas Preston

Preston matriculated west from his Ivy League origins and a wage slave job in the Museum of Natural History. The second half of his life has been a literary immersion in the culture, folklore, and mythology of the desert Southwest. In this nonfiction wilderness romp, he caps off years of research into the early expeditions of the Spanish Conquistadors with a horse pack trip that re-traces the 1540 journey of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, when he went in search of the legendary Seven Cities of Gold.

The Best of the West: An Anthology of Classic Writing from the American West edited by Tony Hillerman

Hillerman, long considered one of the great literary lions of the Rocky Mountain West, made his reputation by writing a series of eighteen mystery novels set on the Four Corners region and featuring a pair of First Nation lawmen, Lt. Joe Leaphorn and Sgt. Jim Chee. This anthology, Best of the West, is trove of stories and excerpted works by explorers and historians (Meriwether Lewis, John Wesley Powell), indigenous voices (N. Scot Momaday, Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé), and eloquent fictional wordsmiths (Wallace Stegner, John Steinbeck, Dorothy Scarborough).

Everett Ruess: His Short Life, Mysterious Death, and Astonishing Afterlife by Philip L. Fradkin.

Into the Wild has been elevated to a scholastic classic. Students captivated by the doomed vagabond Chris McCandles might also enjoy Everett Ruess. Ruess was twenty years old in 1934 when he vanished into the canyonlands of southern Utah, spawning the myth of a romantic desert wanderer that survives to this day.

Learn more about Writers in the Schools here.