Margaret Atwood’s signature wit is in full force in this landmark lecture on, as she phrases it, “problems of female bad behavior in the creation of literature.” Novels, she argues, are not moral tracts for teaching readers how to behave. One can almost hear her smile when she says that “art is what you can get away with.” Atwood dissects the cultural expectations of female characters—often a polarity of virtuous or monstrous—noting the struggles that feminist writers face when confronting these conventions. Citing examples such as Euripides’ Medea, Toni Morrison’s The Beloved, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlett Letter, and Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Atwood confronts traditional female literary tropes and the evolution of female characters throughout history. Her insights on the task of negotiating between what the reader, the writer, and even the character may think of as “good” and “bad,” as well as the necessity of creating multi-dimensional female characters, make this a must-listen for readers and writers alike.

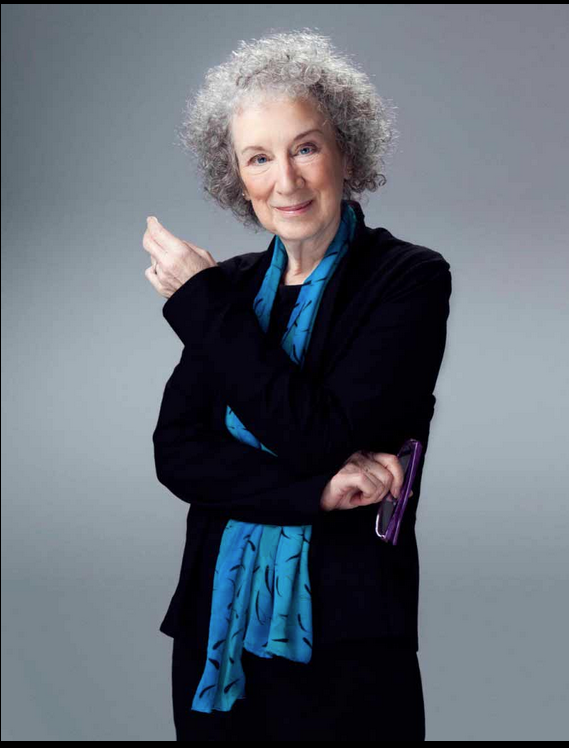

Margaret Atwood was born in 1939 in Ottawa and grew up in Ontario, Quebec, and Toronto. She received her undergraduate degree from Victoria College at the University of Toronto and her master’s degree from Radcliffe College. Atwood is the author of more than 40 volumes of poetry, children’s literature, fiction, and nonfiction, but is best known for her novels, including The Edible Woman (1969), The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), The Robber Bride (1994), Alias Grace (1996), and The Blind Assassin, which won the Booker Prize in 2000. Her latest work is a book of short stories called Stone Mattress: Nine Tales (2014). Her newest novel, MaddAddam (2013), is the final volume in a three-book series that began with the Man-Booker prize-nominated Oryx and Crake (2003) and continued with The Year of the Flood (2009). Her nonfiction book, Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth, was adapted for the screen in 2012. Atwood’s work has been published in more than 40 languages. She currently lives in Toronto with writer Graeme Gibson. (Biography courtesy of margaretatwood.ca/biography)

There is a widespread tendency to judge such characters [in books] as if they were job applicants, or public servants, or perspective roommates, or somebody you would consider marrying. Let me underline the fact that the characters in novels are none of the above—and if they were, we would all be in deep trouble.”

“Novels are made of language, and language, being human, is messy. In short, the novel is ambiguous and multifaceted, not because it is perverse, although it may be that as well, but because it attempts to grapple with what was once referred to as ‘the human condition,’ and it does so using a medium that is as slippery as a greased lawyer, as stretchy as an old-time panty girdle, and as hard to pin down as a bowl of Jell-O—namely, the language itself.”

“The creation of a bad female character doesn’t mean that women should lose the vote.”