by Mel Wells

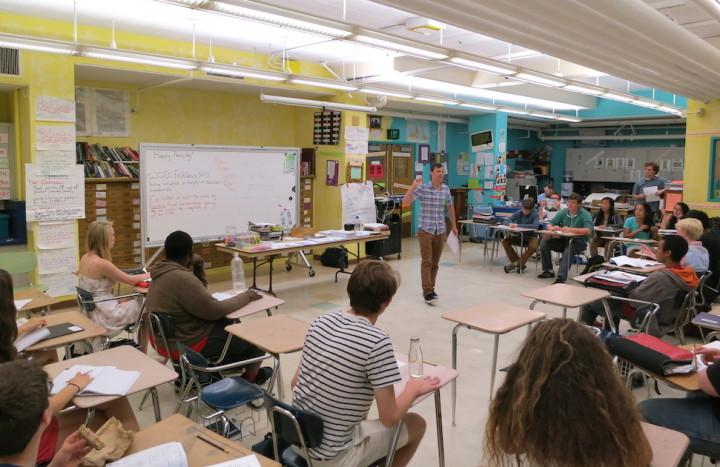

“Your words today are rain, green, sparkle, and cedar tree,” said WITS writer-in-residence Carter Sickels to a classroom of twenty-plus freshman. He turned on music as the students leaned over their papers and began to write, which was the only sound in Dylan Leeman’s classroom at Grant High School for the next several minutes.

All freshman at Grant take Writers Workshop, and WITS placed several writers-in-residence in these classes to help students produce, revise, and refine their creative writing. Carter Sickels, a fiction writer, worked in two sections of Mr. Leeman’s classes.

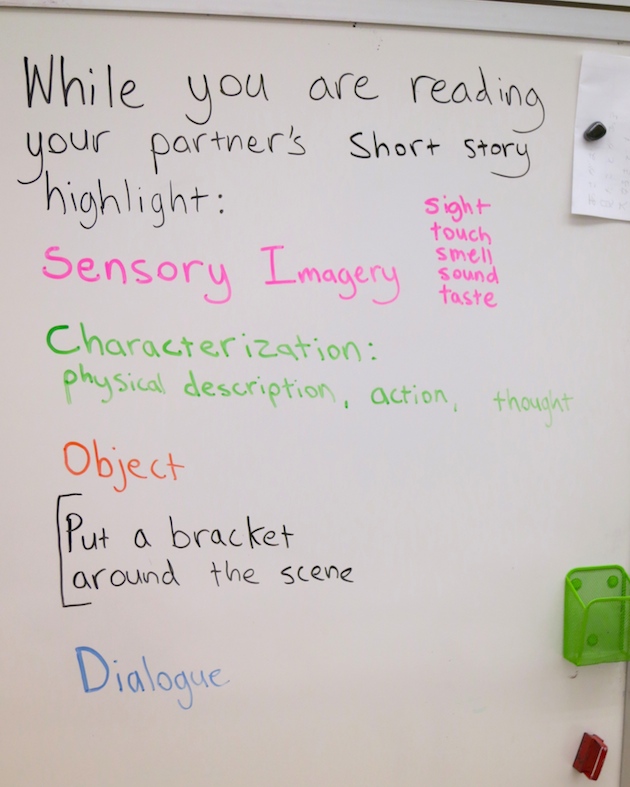

After getting warmed up with the free-write, students pulled out the pieces they had been working on and got into groups for peer editing. Each person was equipped with highlighters, and Carter asked them to identify sensory imagery, characterization, objects, and dialogue in different colors. As students worked together, Carter, Mr. Leeman, and student teacher Mr. Wilson all circulated throughout, giving students valuable one-on-one attention.

One student had a moment of shyness when Carter approached him and asked about his piece.

“You know, when you turn it in, I’m going to read it,” said Carter, smiling.

The student began to laugh. “Okay, you’re right,” he replied. “So there’s this guy…” He launched into a detailed explanation.

“That’s great,” replied Carter. “And you have a strong beginning; now bring in all those details you just told me.”

When I asked Carter about working with freshman, he noted that the students were much more at ease telling him about their ideas than fleshing them out in writing. “I try to get them to translate their ideas to words, and to steer their ideas toward more nuanced explorations of character and objects.”

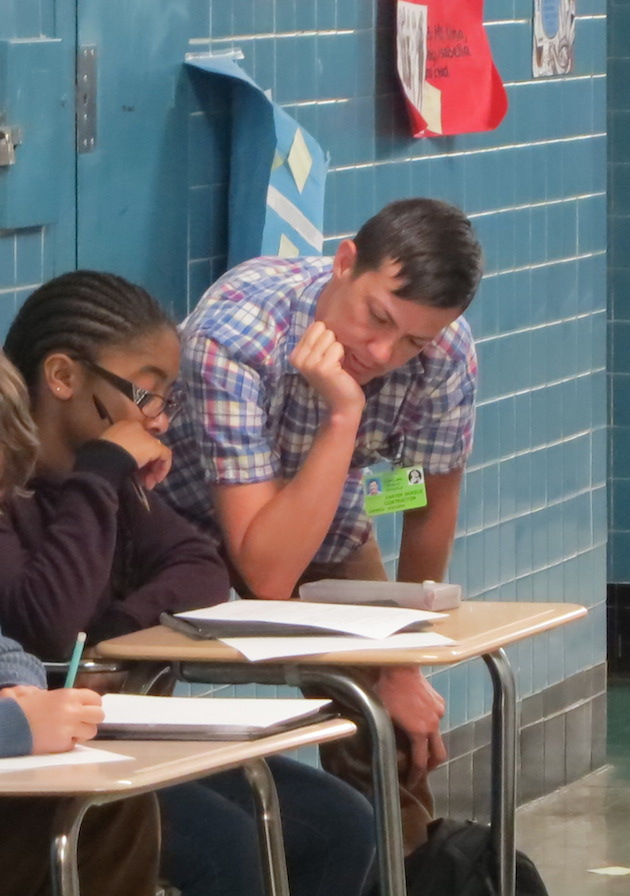

Carter spent most of the class circling the room, listening and offering feedback to several students. “You’re doing something really complicated here,” he said, leaning over one student’s paper, “shifting from past to present. I would keep it in the present for a little longer. It adds tension when readers don’t know the whole story right away.”

Students nodded, asked more questions, and made notes on their papers as they discussed characterizations, motivations, and using objects as symbols.

Finally Carter addressed the entire class, explaining approaches for capturing readers’ attention right away. “Introduce a conflict, a desire, or something different about the day,” he said. “Make your character’s desire clear in the first sentence, and do it with an action or an image.” He had students write a brand-new opening sentence for their piece using this advice. “Experiment,” he challenged them. “Try something radically different.”

And they did.