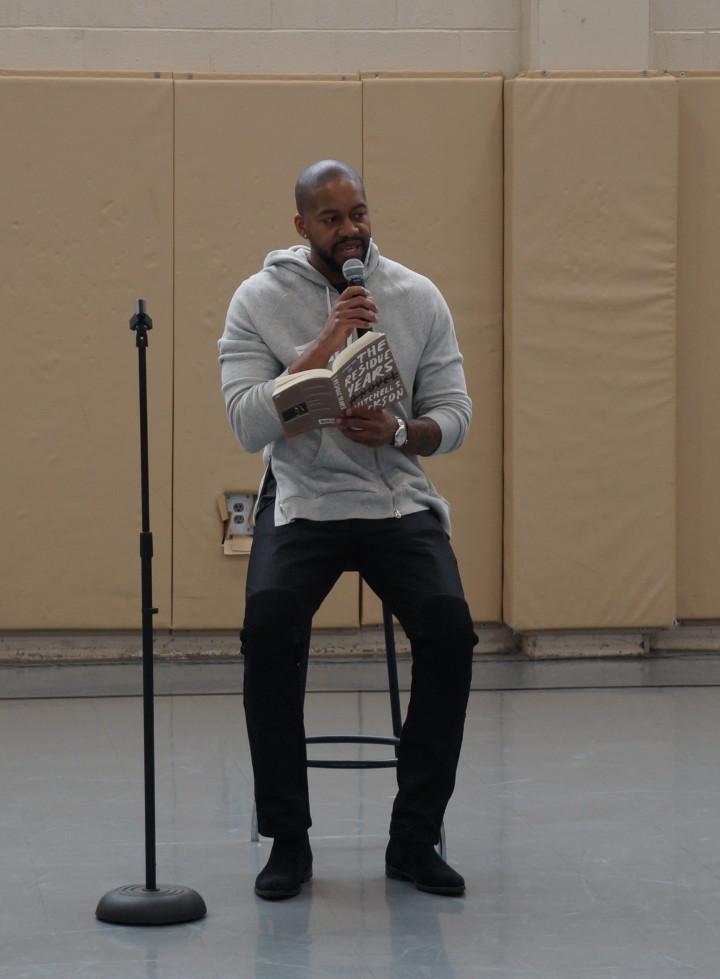

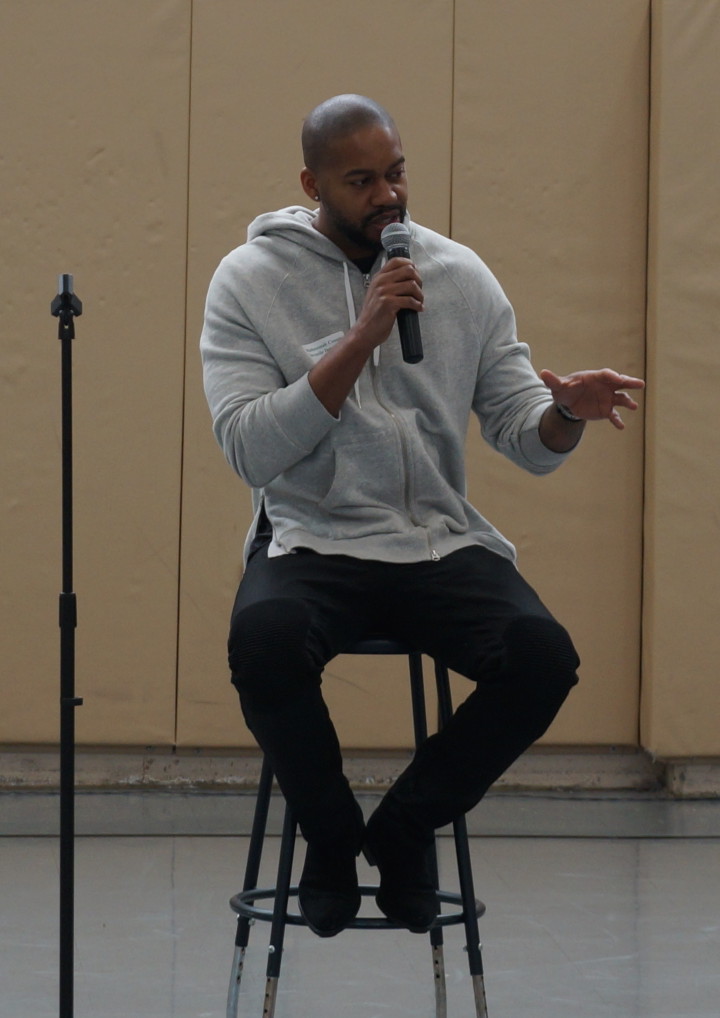

[by Stephanie Wong Ken] As part of the Everybody Reads program, featured author Mitchell S. Jackson visited two schools, the Donald E. Long School and Reynolds High School. Jackson, who was born and bred in Portland but now lives in Brooklyn and teaches in the writing program at NYU, is the author of The Residue Years. The novel focuses on the lives of Grace, a recovering addict, and her son, Champ, who is hustling drugs on the streets of Portland and ends up in prison. Jackson has referred to the novel as “semi-autobiographical” and soon after he greeted the audience with a “What’s up, y’all,” and “It’s good to be back home in my city,” he explained the genesis of the novel.

“I’m from the old NE Portland, from the 1980s,” he said. “Normally, if you have a stable childhood, you go to one high school. But my childhood wasn’t very stable. My mother had a drug addiction since I was ten years old, and I lived with my biological father for a while because my mother went to prison. From the time I was eighteen to the time I was twenty-one years old, I was a drug dealer. But I got caught and went to prison for sixteen months.”

Though Jackson was quick to point out that the audience may or may not relate to his experiences, it was clear from the rapt attention in the room that Jackson’s story hit close to home.

“Was it worth it to be a drug dealer?” A young girl asked.

“Honest truth?” Jackson said. “Yes. I was broke. Dealing gave me the means to go out and support my family. It was like a test, like a crucible, to see how strong I was. Was it right to sell drugs? Absolutely not. Would I advise anyone to sell drugs? Absolutely not. But it taught me my limits.”

“Did you read a lot growing up?” A young man asked at the front of the room.

“I was a writer before I was a reader,” Jackson responded. “When my mom would leave, I would write in my journal. I was using my writing as a catharsis. I always loved to write, but I never really engaged with books growing up. I did enjoy writing what was going on in my life.”

Jackson then explained how he started writing the novel when he was in prison in 1998. It took him over ten years to finish it. “When I was in prison, I thought: my life is going to be a bestseller. Initially, I decided to write fiction because I was talking about people doing bad things and I didn’t want to out them.” He admitted that once he got out of prison, it was difficult to readjust. An academic scholarship from PSU and hard work helped Jackson move forward. “I didn’t want to be the dude who went back to prison. When I was in school, I worked at the Oregonian, but not as a writer. I worked in the mailroom. I would lift and stack the newspapers. While everyone else was out, I was stacking papers on Saturday nights. But I would rather have done that than another shot in prison.”

“What motivated you?” A young audience member asked.

“I always believed I was exceptional,” Jackson answered. “We tend to believe, ‘Well this is the life I was given, this is the life I earned.’ But the thing with growing up at-risk is you have to believe you are the exception, not the rule.”

Jackson told the audience that aspiring writers should “write from their wound.” “Figure out the story you’re afraid to tell, the place you’re afraid to face or talk about. And be willing to learn how to write. It’s a craft, a process. And though every one of us has a story, not everyone can write.”

As the talk wound down, one audience member asked about Jackson’s many tattoos. He rolled up his sleeves to show them images of his mother, his daughter, his son, a coat of arms for Portland, and script that reads “Luminous Days,” which was an alternate title for The Residue Years.

One of the last questions came through a translator, from a young man who spoke Spanish: “How do you get away from the image of being a drug dealer?”

“Learn the King’s English,” Jackson advised, “Everyone in this room should learn how to code switch—to alter your speech based on whom you are speaking to. You’ll speak differently to your mother than you would to your homeboys. So it’s important to learn how to speak to people because they are going to judge you based on how you speak to them. Use the language of power.”

Note: After these school visits, Mitchell Jackson lectured at the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall that evening to an audience that included hundreds of high school students and students from Portland State and Portland Community College. He spoke of revisions, both of books and of the ways we see our lives, and encouraged the audience to help younger members of their community who may be on the wrong path to “re-envision their lives.” By the end, the audience gave him a standing ovation. Mitchell’s lecture will be broadcast on OPB on May 20, 2015 and will become part of The Archive Project on Literary Arts’ website at https://literary-arts.org/archives/.