We’re thrilled to introduce the 2022 Oregon Literary Fellowship recipients with individual features on our blog! Out-of-state judges spent several months evaluating the 400+ applications we received, and selected nine writers and two publishers to receive grants of $3,500 each. Literary Arts also awarded two Oregon Literary Career Fellowships of $10,000 each. The 2023 OLF applications are open now. The deadline to apply is Friday, August 5, 2022.

Rebecca Bornstein has held many jobs– including production cook, elementary school secretary, goat sitter, and creative writing instructor. She holds an MFA from North Carolina State University, and her poetry has appeared in Tinderbox Poetry Journal, The Baltimore Review, jmww, The Boiler, The Journal, and elsewhere. She’s currently at work on her first poetry collection.

Category: C. Hamilton Bailey Fellowship – Poetry

Pronouns: she/her

Q&A with Literary Arts

Who are some writers you look up to or who move you to write?

Number 1 is my mentor and “poetry mana,” Dorianne Laux. Her poetry is so lovingly human– funny and wry and earnest, grounded and searching, equally interested in both the minutiae and the huge mystery of being alive. Hers is the voice I’m writing toward, and that I hear when I am editing my own work, pushing me along to make the poem better and more true. I also greatly admire the work of Phil Levine, Lucia Perillo, June Jordan, and Jan Beatty, who gave me some of the best advice I’ve received as a poet, which was to “write the scary poems.”

What are your sources of inspiration? Of joy?

I love comedy– sketch comedy, stand-up, improv. The world can feel so dark and heavy, and comedy can acknowledge that darkness while at the same time providing relief and release. I think that poetry and comedy are so related– they rely on compressed and controlled language to say something more true than can be stated directly, and the most successful poems or jokes cause a visceral reaction. I’ve never written a successful joke, but I hope to someday!

How would you describe your creative process?

Really drawn-out, compared to most poets. I don’t have much time to write, and I edit really slowly, so I’m often working with drafts that are more than a year old. I write almost all of my first drafts by hand, in a notebook, and when I end up with something I know I want to keep working with, I transfer it to the computer. It used to be that only completed drafts that needed to go to the computer (to submit, etc) got transferred, but the computer is creeping earlier into my process, for better or worse.

I also write a lot to exercises– both exercises that have been given to me by other people, and through an infinitely reusable exercise I learned from Dorianne during my time at North Carolina State. At its simplest, this exercise involves picking up the book that’s closest to you, and flipping through to randomly collect 10 words– the first word your eye lands on when you open a page. If you want an added challenge, you can use either that book, or a second book, to find a random phrase (I usually shoot for 3-5 words). Optionally, you can also include some rules, which can be as easy or challenging as you want them to be (for example “write in tercets,” or “start with an image” or “include a lesser-known piece of furniture”). Then set a timer for 20 minutes and write a poem! The point of the exercise is to take you to an unexpected place, so it’s not a problem if you don’t follow all of the rules or use all of the words. I’ve written dozens, if not hundreds, of poems using this exercise and it never gets old.

What is most exciting about receiving a fellowship?

The award has given me the opportunity to invest in myself as a writer in ways that would not have been accessible otherwise. Because of this fellowship, I am able to apply for writing residencies, chapbook contests, and submissions to literary magazines which charge fees, all of which I was previously unable to regularly afford. And intrinsically connected is the validation the fellowship provides– so not only the practical level of being able to pay fees, etc that I could not have afforded without the fellowship– but this extra confirmation that my work is worth investing in.

What are you currently working on?

I have recently completed a chapbook manuscript, which I am currently submitting. In completing that manuscript, I discovered that I have this other group of poems that didn’t belong in the chapbook, and which I hope are the first seeds of a full-length manuscript.

What has kept you writing through the pandemic? Has your process changed? Has the content changed?

I wrote very very little during the first year of the pandemic. I struggle with anxiety, so I spent much of 2020 just kind of refreshing my news feed and hoping that society and/or our healthcare system didn’t collapse. To some degree, I still feel like I’m doing that, but I have managed to weave writing back in. Whether or not it has to do with the pandemic specifically, my writing has become more political. More and more, I feel myself writing towards the question that Czeslaw Milosz poses in his poem, “Dedication”– “What is poetry which does not save / Nations or people?”– or maybe to the other side of that question, which is “How can poetry save nations or people?” I don’t know the answers to the question, or if it’s even answerable, but it feels urgent to ask.

“What is poetry which does not save / Nations or people?”

Czeslaw milosz

What advice do you have for future applicants?

Apply, and keep applying, even if you think you have no chance! When I applied, I felt like it was a long-shot, pie-in-the-sky situation. You never know who your work might resonate with.

Any book (or movie, show, album, etc. ) recommendations?

1. I recently read Lynn Melnick’s latest collection of poems, “Refusenik,” and it was exactly what I needed. Also “Citizen Illegal,” by Jose Olivarez, which I can’t stop re-reading. In a way, I see both of these collections as in conversation with that Milosz question.

2. I’m going to second fellow fellowship recipient Clementine’s mention/recommendation of “In the Dream House” by Carmen Maria Machado. The footnotes and the way the book connects to classic tropes changed what I thought a memoir could be or do.

3. I cannot get enough of Fiona Apple– if you haven’t listened to Fetch the Bolt Cutters, you’re missing out! She’s one of the most poetic lyricists I’ve ever heard.

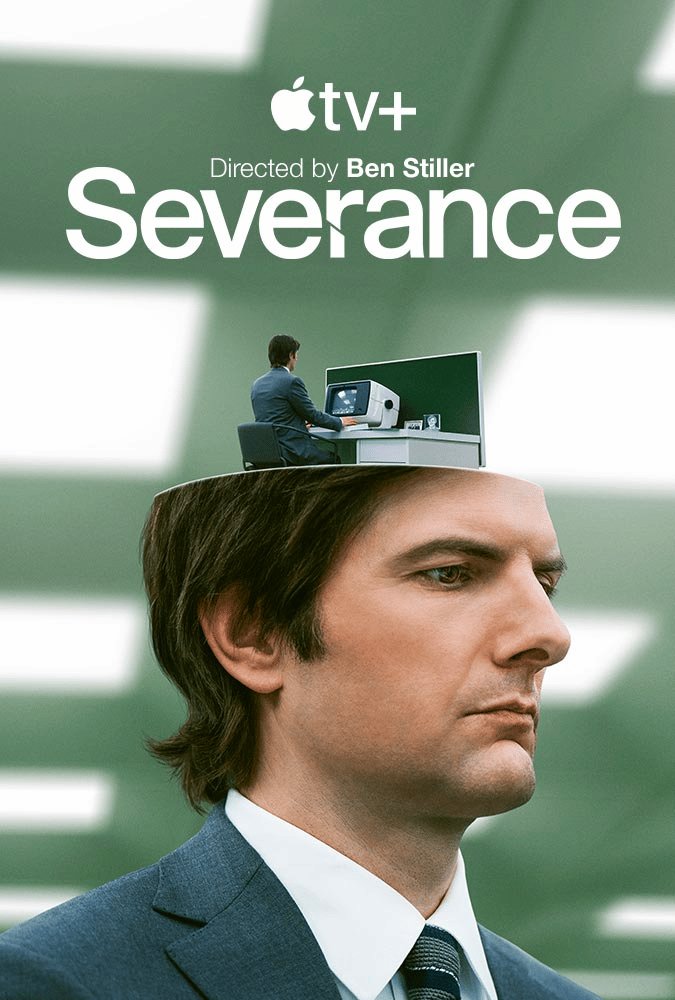

4. I’m also obsessed with the tv show Severance. It’s a dystopic sci-fi about a group of people who have undergone a procedure that permanently mentally separates their work selves from their outside-of-work selves, and it’s incredibly well-written and well-acted, in addition to being funny and creepy and so surprising that it caused me to literally gasp more than once.

5. I have to end with a comedy recommendation– the Kids in the Hall have reunited and released a new season of their classic sketch comedy show, which has all the goofiness, irreverence, and charm of the original. Kids in the Hall is one of the things I put on when I feel like I can’t face the world, and it always makes me laugh and laughing always makes me feel a little better.

Most of the Middle School Girls I Knew

Most of the middle school girls I knew were mean

because they had to be, because they had older brothers

and their Catholic mothers refused to buy them bras

even though they needed them, and they were embarrassed

by their grandparents who lived there, too. They were mean

because their fathers favored their brothers, or else their stepfathers

snuck obvious peeks at their friends changing into pajamas

during sleepovers. Most of the middle school girls I knew

had mothers who worked as bartenders, or waitresses,

or third shift at the Tyson factory, where they spent their nights

inspecting an endless conveyor of chicken thighs, pale as ghosts.

At lunch, they ate thin sandwiches on white bread.

Most of the middle school girls I knew spent hours watching,

in houses where the television was an extra sibling to attend to,

where you got up to turn down the volume for dinner.

We watched the middle school boys practice violence and sports,

watched the neighborhood children for less than minimum wage,

watched everyone to see who was looking, and when, and why.

Most of the middle school girls I knew lied about their periods,

insisting they’d got theirs, or else filching tampons and telling no-one.

They were tough– they’d been drunk and in fights–

they wore their hair pulled back tight so nobody could pull it,

shoplifted candy and lip gloss from the dollar store,

shared deep and knowing stares of hatred with security guards.

We each took turns with the stolen gloss’s syrupy wand

in the very back seat of the school bus before kissing the same boy,

confident and blonde as a lion. His goal was to rank us.

Most of the middle school girls I knew skipped their homework,

but I did mine, little suck-up, and when my teacher still didn’t like me,

I cried. But most of the middle school boys I knew copied mine–

it was how I got popular– so I practiced my petty defiance and

shared cigarettes pilfered from the littered purses of the mothers

of most of the middle school girls I knew, who smoked

Camels or Newports at night at the kitchen table or on the back porch,

when us girls slunk home to find a worried mother waiting,

one flannel-clad arm folded into the crook of the other,

bags under her eyes and thick ankles, pondering which checks

to float that month, her cigarette cherry glowing beacon-red

with each inhalation of the inky, buzzing night.

Judge’s Comments

“ ‘What we can’t transform becomes an archive,’ could be the anthem of Rebecca Bornstein’s poems. This is not an archive filled with the precious, but rather hunger, callouses, leftovers, bad jobs, and alternate endings. These poems brim with heart, brio, and with a ‘disgusting hope’ dare to assemble something worth remembering. I won’t soon forget these poems that stand as a defiant record of how we live around, and for, and through what we can’t change.”

– Tomás Q. Morín